This is part-1 of an article, being published to mark the Birth Anniversary on April 14, of Dr. BR Ambedkar (1891-1956).

Referring to “a great deal of controversy” regarding the origin of caste, “as to whether it is due to the conscious command of a Supreme Authority, or is an unconscious growth in the life of a human society under peculiar circumstances,” Dr. BR Ambedkar says: “Those who hold the latter view will, I hope, find some food for thought in the standpoint adopted in this paper.”

The above is the concluding para (no.47) of a Thesis of 47 paras by Ambedkar: CASTES IN INDIA: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development, a Paper he presented on 9th May 1916 at an Anthropology Seminar at Columbia University. That was one of his earliest significant works, a scholarly work; written by the scholar when he was 25, much before he became a politician.

(emphases added, throughout this aticle, unless otherwise indicated.)

Unconscious growth, he wrote. In an earlier para 34, he explicitly refutes the theories about “conscious command of a Supreme Authority” and wrote: “Manu, the law-giver of India, if he did exist, was certainly an audacious person…One thing I want to impress upon you is that Manu did not give the law of Caste and that he could not do so. Caste existed long before Manu. He was an upholder of it and therefore philosophised about it, but certainly he did not and could not ordain the present order of Hindu Society. His work ended with the codification of existing caste rules and the preaching of Caste Dharma…”

“The spread and growth of the Caste system is too gigantic a task to be achieved by the power or cunning of an individual or of a class. Similar in argument is the theory that the Brahmins created the Caste. After what I have said regarding Manu, I need hardly say anything more, except to point out that it is incorrect in thought and malicious in intent. The Brahmins may have been guilty of many things, and I dare say they were, but the imposing of the caste system on the non-Brahmin population was beyond their mettle. They may have helped the process by their glib philosophy, but they certainly could not have pushed their scheme beyond their own confines. To fashion society after one’s own pattern! How glorious! How hard!”

The above lines go against the popular notions about the origin of caste, ascribed to Ambedkar, and repeated by all and sundry without respect to his above-stated view.

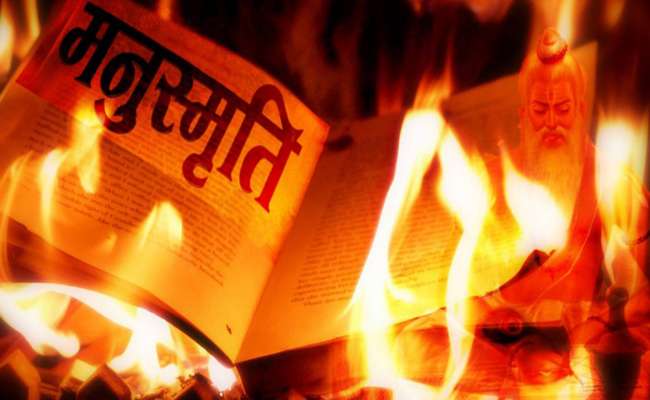

The popular notion is perhaps rooted in this well-known fact: on 25 December 1927, the book of Manusmriti was publicly burnt…see these recorded details: Manusmriti was placed on a pyre, in a specially dug pit, and ceremoniously and symbolically burnt, ironically with sandalwood, and with only one photo, of Gandhiji in the pandal, by Ambedkar and his colleagues… burnt at the hands of Sahasrabuddhe, the Brahmin friend of Dr. Ambedkar, who had negated the theory that Brahmins created the Caste…

While reviewing some ideas on caste till then prevalent, Ambedkar concludes his thesis with the following lines indicating his scientific method, his conviction, and open-mindedness as an young scholar:

“The primary object of the paper is to indicate what I regard to be the right path of investigation, with a view to arrive at a serviceable truth. We must, however, guard against approaching the subject with a bias. Sentiment must be outlawed from the domain of science and things should be judged from an objective standpoint….To conclude, while I am ambitious to advance a Theory of Caste, if it can be shown to be untenable I shall be equally willing to give it up.”

He did not give up, but continued to uphold the above views: Ambedkar himself published his famous work, Annihilation of Caste, in 1936, and its third edition in 1944, in which he included this Thesis of 1916, with no revisions, thus basically upholding it, even subsequently.

“A Caste is an Enclosed Class,” Ambedkar famously said. Some use him to deny the class basis of caste. Here is the relevant para:

“[31] ….To say that individuals make up society is trivial; society is always composed of classes. It may be an exaggeration to assert the theory of class-conflict, but the existence of definite classes in a society is a fact. Their basis may differ. They may be economic or intellectual or social, but an individual in a society is always a member of a class. This is a universal fact and early Hindu society could not have been an exception to this rule, and, as a matter of fact, we know it was not. If we bear this generalization in mind, our study of the genesis of caste would be very much facilitated, for we have only to determine what was the class that first made itself into a caste, for class and caste, so to say, are next door neighbours, and it is only a span that separates the two. A Caste is an Enclosed Class.”

No amount of preaching by the priests can create it, he says and adds, no amount of preaching by the reformer can unmake it! His approach is based on material facts, materialist outlook. The Indian Constitution also preaches, but could not annihilate caste as desired by him and other reformers. Even untouchability is not totally eradicated, 70 years after the Constitution came into effect.

( see for more on this topic: Re-Reading Dr BR Ambedkar’s Earliest Paper On Caste 100 Years Later, by Dr KS Sharma, June 18, 2016)

*** ***

The “unconscious growth” did not spare any community in British India

In this Thesis he as a sociologist indicates how caste was a characteristic phenomenon in the then (British) India of 1916, which is by and large co-terminus with South Asia today, which includes Pakistan and Bangladesh with predominantly Muslim population, Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Srilanka) with Buddhists, apart from the Portuguese colony of Goa, with Christians.

In para 44, he wrote: … “Take India as a whole with its various communities designated by the various creeds to which they owe allegiance, to wit, the Hindus, Mohammedans, Jews, Christians and Parsis. Now, barring the Hindus, the rest within themselves are non-caste communities. But with respect to each other they are castes.”

Though he wrote “within themselves are non-caste communities,” when we probe a little, we find many things : Even today, we can see in many villages how people of religions other than Hindus are identified as “another caste” rather than as (merely) of a different religion. In particular , Muslims and Christians are treated as another caste in view of conversions of recent past.

One can find some in the same kith and kin being converted as Christians, while some others remaining as Hindus; there are marriages too among them, caste being the same; and post-marriage, there is informal reconversion too. Post-conversion too, they continue with customs they inherited from their past as Hindus and often with an added imprint of their caste. Christians of one caste (say Nadar or Reddy) do not normally marry Christians of another caste (say Kapu or vanniar). The matrimonial Ads are explicit about it. That is, the real identification is more with caste rather than as Christians.

*** ***

Dr. BR Ambedkar on caste and caste discrimination among muslims

Caste in India is very much seen also beyond Hinduism, beyond Brahminism, and beyond Manu. If we see caste as merely linked to Hinduism, Brahminism or Manu, we in fact under-estimate its deep, vicious, divisive and diversionary role in society and polity.

Thus Ambedkar in his Thesis of 1916 laid the foundations for such an approach. “Sentiment must be outlawed from the domain of science and things should be judged from an objective standpoint,” he said. He stressed endogamy, the key feature found among Christians and Muslims too. Caste in Indian Christians, however, is relatively more explicit than among Muslims.

Further Dr Ambedkar opines thus: “Take the caste system. Islam speaks of brotherhood. Everybody infers that Islam must be free from slavery and caste. Regarding slavery nothing needs to be said. It stands abolished now by law…But if slavery has gone, caste among Musalmans has remained…There can thus be no manner of doubt that the Muslim Society in India is afflicted by the same social evils as afflict the Hindu Society”.

On the basis of the Census Report 1901, Dr Ambedkar notes about the Dalit Muslims: “With them no other Mahomedan would associate, and they are forbidden to enter the mosque or to use the public burial ground”.

In contrast to the social reform movements to combat caste among the Hindus, Dr Ambedkar feels that: “The Muslims…do not realise that they are evils and consequently do not agitate for their removal. Indeed, they oppose any change in their existing practices” (Dr B. R. Ambedkar, Pakistan or the Partition of India, Kalpaz Publications, Delhi, 1945, pp. 218-223).

(Quoted by Khalid Anis Ansari in his article in theprint.in 13 May, 2019. More about it later.)

*** ***

Dr. Khalid Anis Ansari on Caste in Muslims of India

We shall, in this part of the article, give a review of the study on caste among Indian Muslims, a taboo subject? We shall presently go into caste among Muslims, which exists even in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

This is necessary if the communal and fascist BJP, a professedly Hindutva party, is to be contained and countered effectively.

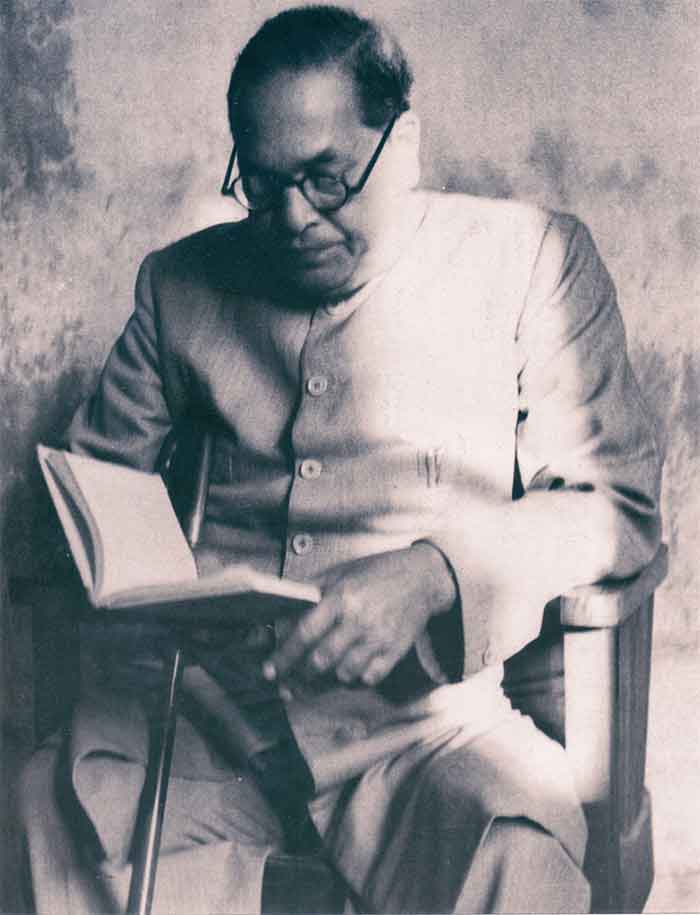

It is to the credit of mainly Dr. Khalid Anis Ansari (see photo below), Director, Dr Ambedkar Centre for Exclusion Studies and Transformative Action, Glocal University, Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh, to bring out the caste among muslims. He advanced Ambedkar’s observations and formulations.

KA Ansari (see his photo below) is one of the few who did deep and consistent study on caste among India’s Muslims, a taboo subject for many. He worked on minority and caste studies, and social histories of the marginalized. He has worked on collaborative research and developmental projects with institutions in UK, the Netherlands, Portugal etc. He has delivered talks in leading international & national institutions like the Harvard University (USA), University of Michigan (USA), University for Humanistic Studies (the Netherlands), Tata Institute of Social Sciences (India). He writes regularly in academic and popular spaces and has been associated with democratic movements in North India as an interlocutor and knowledge activist. (his mail ID : [email protected])

Momin Conference, 1939 Gorakhpur: “the history of caste movements among Muslims can be traced back to the commencement of the Momin Movement,” says K.A. Ansari.

The caste feature is found, less clearly, rather more subtly, among some “lower” communities of Muslims also. For instance, a Khan would not normally marry a Quereshi. The Muslim matrimonial Ads also reflect this to an extent.

There were more than 100 castes, yes castes, listed among muslims of UP, Bihar, Maharashtra etc. a few decades ago. Reservations were extended and implemented to some of these castes among muslims as backward communities in all the states of South as also in Bengal (OBC A and B), despite some legal hitches. Mulayam’s Samajvadi Party promised reservations for muslims. There are demands in other states too from sections of muslims. The Uttar Pradesh-based Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind (JUH) announced to launch a protest rally in Mumbai on April 26, 2015 against the BJP-led Maharashtra government for its decisions such as beef ban and scrapping five per cent reservation to Muslims.

K.A. Ansari wrote in an article in indianexpress.com, March 29, 2018. titled , It’s Not Just Religion, It’s Also Caste :

“What one needs to stress is that there can be no majorities (Hinduness) without minorities (Muslimness) and the mutual conflicts between them eventually end in accommodations that exclude the subordinated castes.”

Identities of religion, and more so of caste, are invariably linked with state and its patronage. He writes:

“Let us recall how the modernising colonial state eventually settled on religion as the overarching identity to manage the irreducible socio-cultural diversity in the Subcontinent through strategic repression of competing markers — caste, class, gender, language, region, sect and so on. In particular, caste approximates the closest to distribution of material and symbolic power. Once this is conceded, it becomes easier to appreciate how the high-caste elite across religions, a micro-minority in number, found it useful to access the evolving democratic game as religious majorities or minorities in order to offset their numerical deficit. In a way, the notions of “Hinduness” or “Muslimness” were systematically arrived at through repression of the cultural life-worlds of a large number of subordinated caste communities.”

Ansari goes into the theoretical and political aspects involved in the extracts given below:

While the left-liberals at times do note that Hindu and Muslim nationalisms share a symbiotic relationship, they seldom take cognisance of the constitutive role of caste in this conflict. Caste, in general, has been a blind spot for left-liberals; more so in the case of Indian Islam.

The moment one inserts caste into the “Muslim question”, the terms of the debate change. Most of the issues raised by the majoritarian Right like the appeasement of Muslims, their portrayal as fifth columnists, Muslim communalism, instant triple divorce, reservations, AMU, Babri Mosque, Urdu, etc. lose their impact once the role of Ashraf interests comes to the fore.

Sans the caste category, left-liberal bickering on the decline of “Muslimness” does not go beyond formal rhetoric. Once the conflation of Muslim politics with Ashraf interests is clear, it is not be difficult to see why the Pasmanda sections may not indulge in mourning the so-called demise of Muslimness but rather see this moment as a rupture pregnant with multiple democratic possibilities.

What one needs to stress is that there can be no majorities (Hinduness) without minorities (Muslimness) and the mutual conflicts between them eventually end in accommodations that exclude the subordinated castes.

That is why the Pasmanda ideologues have advocated a counter-hegemonic solidarity of subordinated castes across religions. Ideally, the left-liberals would have revisited their closures with respect to the caste question within Indian Islam if they were serious about contesting toxic majoritarianism.

One recalls here Dalwai’s collapsing of the distinction between “nationalist” and “communalist” Muslims, or Ambedkar’s conflation of the categories of “priestly” and “secular” Brahmins in explaining the role of social classes in politics. “Muslim communalists in India and Indian communists have always remained strange, but inseparable, bedfellows,” is what Dalwai wrote in the 1960s. Whether the recent debate has done anything to dispel this impression is a moot question. ( Hamid Dalwai in Muslim Politics in India, 1968)

(indianexpress.com, March 29, 2018.)

*** ***

Dr. Ansari in 2009 on Pasmanda Movement

Indian Muslims have about 700 caste groups, says Ansari. He dealt with the related century-old history and politics earlier in another article of 2009, titled, Rethinking the Pasmanda Movement, in the famous journal, EPW. Extracts from it are given below:

“The Pasmanda Movement (PM) refers to the contemporary caste/class movement among Indian Muslims. Though the history of caste movements among Muslims can be traced back to the commencement of the Momin Movement in the second decade of the 20th century (see photo above), it is the Mandal decade (the 1990s) that saw it getting a fresh lease of life. That decade witnessed the formation of two frontline organisations in Bihar – the All India United Muslim Morcha (1993) led by Ejaz Ali and the All India Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz (1998) led by Ali Anwar – and various other organisations else-where.

“Pasmanda, a word of Persian origin, literally means “those who have fallen behind”, “broken” or “oppressed”. For our purposes here it refers to the dalit and backward caste Indian Muslims who constitute, according to most estimates, 85% of the Muslim population and about 10% of India’s population. By invoking the category of “caste”, the PM interrogates the notion of a monolithic Muslim identity and consequently much of “mainstream” Muslim politics based on it.

“By and large, mainstream Muslim politics reflects the elite-driven symbolic/ emotive/ identity politics (Babri Mosque, Uniform Civil Code, status of Urdu, the Aligarh Muslim University and so on) which thoroughly discounts the developmental concerns and aspirations of common Muslim masses.

“By emphasising that the Muslim identity is segmented into at least three caste/class blocks – namely, ashraf (elite upper caste), ajlaf (middle caste or shudra) and arzal (lowest castes or dalit) – the PM dislodges the common-place assumption of any putative uniform community sentiment or interests of Indian Muslims. It suggests that just like any other community, Muslims too are a divided house with different sections harbouring different interests. It stresses that the emotive issues raised by elite Muslims engineer a “false consciousness” (to use a Marxian term) and that this euphoria around Muslim identity is often generated in order to bag benefits from the state as wages for the resultant de-politicisation of the Muslim masses.

“When the PM raises the issue of social justice and proportional representation in power structures (both community and state controlled), for the pasmanda Muslims it lends momentum to the process of democratisation of Muslim society in particular and the Indian state and society in general. Besides, the PM also takes the forces of religious communalism head on: one, by privileging caste over religious identity it crafts the ground for cementing solidarities with corresponding caste/class blocks in other religious communities, and, two, by combating the notion of a monolithic Muslim identity it unsettles the symbiotic relationship between “majority” and “minority” fundamentalism. In short, the PM holds the promise of bringing Muslim politics back from the abstract to the concrete, from the imaginary to the real, from the heavens to the earth!”

Then he adds: “But despite these brave promises the PM has been unable to create the impact that was expected of it.” That is a subject by itself, beyond the scope of this article. He states: “Right from the days of the All India Momin Conference (its pre-eminent leader being Abdul Qayyum Ansari) way back in the 1930s to its present post-Mandal avatars, the PM has singularly concentrated on affirmative action (now the politics around Article 341 of the Constitution) and electoral politics at the expense of other pressing issues.”

(Rethinking the Pasmanda Movement, EPW Commentary, Vol. 44, Issue No. 13, 28 Mar, 2009)

*** ***

“Caste-based discrimination prevalent in the Muslim society”

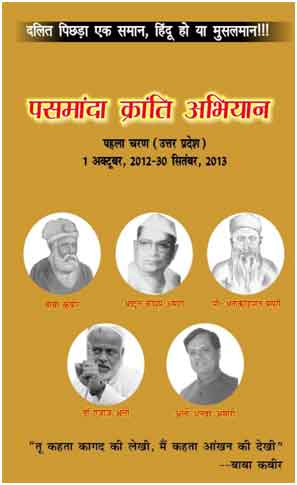

A poster of the Pasmanda Kranti Abhiyan,2012-13. Slogan on top reads – Dalit & Backwards are same – whether Hindu or Muslim.

In an article in theprint.in , 13 May, 2019, titled India’s Muslim community under a churn: 85% backward Pasmandas up against 15% Ashrafs, Ansari brought out many social and political aspects. Given below are extracts from it:

“Indian Muslims, too, are victims of caste-based stratification, and are divided into three main classes and hundreds of biradaris. At the top of the hierarchy are the ‘Ashraf’ Muslims who trace their origin either to western or central Asia (for instance Syed, Sheikh, Mughal, Pathan, etc or native upper caste converts like Rangad or Muslim Rajput, Taga or Tyagi Muslims, Garhe or Gaur Muslims, etc). Syed biradari is highly revered and their status is almost symmetrical to the Brahmins in Hinduism.

“The philosophy of social inequality within Muslims is termed Syedism, and movements against the Ashraf dominance have been led by the ‘lower’ ones — Ajlaf (backward Muslims) and Arzal (Dalit Muslims)—at least since the beginning of the 20th century.”

Pasmandas’ slogan of 85% vs 15% against Syedwad is making backward Muslims talk about rights instead of virtue, dawa instead of dua.

The savarna Muslims constitute about 15 per cent of the entire Muslim population in India, while the rest comprise the backward, Dalit and tribal Muslims.

The 1990s saw the rise of several social movements that gave voice and a new direction to abolish casteism in the Muslim society with several organisations leading from the front — the All India Backward Muslim Morcha of Dr Ejaz Ali, and the All India Pasmanda Muslims Mahaj of Ali Anwar from Bihar, and the All India Muslim OBC Organisation of Shabbir Ansari from Maharashtra.

Two books – Ali Anwar’s Masawat Ki Jung (2001) and Masood Alam Falahi’s Hindustan Mein Jaat Pat aur Musalman (2007) – were especially instrumental in exposing the caste-based discrimination prevalent in the Muslim society. These books demonstrated how the Ashraf Muslims had hegemonised and were over-represented in Islamic organisations and institutions (Jamat-e-Ulema-e-Hind, Jamat-e-Islami, All India Muslim Personal Law Board, Idaar-e-Sharia etc.), government-run institutions for minorities (Aligarh Muslim University, Jamia Milia Islamia, Maulana Azad Educational Foundation, Urdu Academy etc.) and power structures generally.

The books also illustrate the many layers and forms of caste-based discrimination that is practised in the Muslim society — caste-based endogamy and observation of social distance, the mocking or taunting of subordinate caste Muslims, the existence of separate burial grounds, the practice of forcing lower Muslims to stand in the back rows during Namaz prayers in certain regions, and the practice of untouchability against Dalit Muslims among others.

It is the result of such literature and efforts of the aforementioned organisations that the backward, Dalit and tribal Muslim communities — Kunjre (Raeen), Julahe (Ansari), Dhunia (Mansuri), Kasai (Qureishi), Fakir (Alvi), Hajjam (Salmani), Mehtar (Halalkhor), Gwala (Ghosi), Dhobi (Hawari), Lohar-Badhai (Saifi), Manihar (Siddiqui), Darzi (Idrisi), Vangujjar, etc. — are now organising under the identity of ‘Pasmanda’: the ones who have been left behind.

The politics arranged around the axis of religion is often employed by the Brahminical and Syedist forces to protect their own interests and social dominance.

Incidents of mob lynching and communal riots are often sponsored and orchestrated by these forces to trap the subordinate caste communities in the web of emotional issues, thereby suppressing the far more pressing issues of the latter’s social and economic upliftment.

In a way, the Hindu and Muslim communal forces are hand in glove and feed on each other. The victims in nearly all communal incidents are almost always the subordinate castes while the beneficiaries are the forward caste sections.

It is somewhat perplexing that a population otherwise divided into hundreds of castes and communities is precipitously transformed into “Hindu” and “Muslim” during communal incidents and riots.

The real numerical minority – the upper caste Hindus and Muslims – has successfully captured Indian democracy by deploying the secular-communal and majority-minority binaries based on religious identity. That is why the Pasmanda movement insists on social identity instead of religious identity.

Questions are being raised about the representation of Pasmanda Muslims in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. As per one analysis, of the 7,500 elected representatives from the first to the fourteenth Lok Sabha, 400 were Muslims — of which 340 were from Ashraf (upper caste) community. Only 60 Muslims from the Pasmanda background have been elected in fourteen Lok Sabhas. As per 2011 Census, Muslims constitute about 14.2 per cent of India’s population. This means that Ashrafs would have a 2.1 per cent share in the country’s population. But their representation in the Lok Sabha was around 4.5 per cent. On the other hand, Pasmandas’ share in the population was around 11.4 per cent and still they had a mere 0.8 per cent representation in Parliament.

Whenever Pasmanda Muslims try to contest an election, the Ashraf Muslims taunt them as Dhunia, Julaha, Kalal, Kunjra or Kasai. They make all efforts to ensure their defeat. On the other hand, whenever an Ashraf candidate is fielded, voting for him and ensuring his victory is termed as an Islamic responsibility and virtue.

Manyawar Kanshi Ram had once narrated his experience of working with Indian Muslims:

“I thought it was better to contact Muslims through their leadership. After meeting about 50 Muslim leaders I was astonished to witness their Brahmanism. Islam teaches us to establish equality and struggle against injustice but the leadership of Muslims is dominated by so-called high castes like Syeds, Sheikhs, Mughals and Pathans. The latter do not want the [subordinated Muslim castes like] Ansaris, Dhuniyas, Qureshis to rise to their levels…I decided to groom only those Muslims who had converted from Hindu SC communities [Pasmanda Muslims] for leadership” (Satnam Singh, Kanshi Ram ki Nek Kamai Jisne Soti Qaum Jagai, Samyak Prakashan, New Delhi, 2007, p. 132). Even Ambedkar and Ram Manohar Lohia have categorically acknowledged casteism within Muslim society.

In the same vein, Ram Manohar Lohia suggests: “India’s politicians have hitherto not cared to promote the interests of the really oppressed minorities of the country, the numberless backward castes among Hindus as well as Muslims. They have served the cause of the strong on the pretext of their being a minority, the Parsi, the Christians, the high castes among Muslims as also among Hindus” (Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, Guilty Men of India’s Partition, B. R. Publishing Corporation, 2000, Delhi, p. 47).

The Pasmanda community is now talking about politics of rights instead of sawab (virtue/piety), and dawa (medicine/healthcare) instead of dua (supplication)… The politics of marginalised communities is akin to lava burning for centuries below the earth’s surface.

*** ***

Abhay Kumar on the history and politics of the Pasmanda

Dr. Abhay Kumar of JNU, familiar to readers of countercurrents.org, is another scholar who wrote more on the subject. Citing Khalid Anis Ansari, Kumar in an article of 2015-16, titled Bahujan first, then Muslim, briefly sketched the history and politics of the PM. Following are extracts from it:

| By making common cause with other Dalits and Backwards and adopting new icons, the Pasmandas have broken free from the grip of elite and casteist minority politics.. |

Ever since the emergence of Pasmanda movement on the large political scene in the 1990s, traditional minority politics has come in for sharp criticism from the new cultural imaginary. Influenced by Mandal politics (1990s), the Pasmanda movement has not only questioned the hegemony of ashraf (upper-caste) Muslims but also succeeded in rewriting history and replacing the symbols and idioms of “elite” minority politics…

Examples of some well-known Pasmanda castes are Lalbegi, Halalkhor, Monchi, Pasi, Bhant, Bhatiyara, Pamriya, Nat, Bakkho, Dafali, Nalband, Dhobi, Sai, Rangrez, Chik, Mirshikar and Darzi.

Simply put, Pasmanda Muslims are Backwards (Shudra) and Dalits (Ati-shudra) who embraced Islam centuries ago to free themselves from caste atrocities. But the change of religion did not liberate them from caste discrimination and material deprivation.

Despite the fact that Islam underscores equality and brotherhood, there are often media reports of Dalit Muslims being denied entry to mosques and graveyards by ashraf Muslims. Besides, inter-caste marriages in Muslim society are also not common.

Thus the Pasmanda leaders lay more emphasis on their Dalit and backward identity than their Muslim identity, questioning the idea of Muslims being a “monolithic” community. In recognition of the caste discrimination among Muslims, Pasmanda politics aims at arriving at a broader “Bahujan unity” of Dalits and Backwards across religions…

Pasmanda intellectual Khalid Anis Ansari has divided the Pasmanda movement into two phases. While the second phase was the byproduct of Mandal politics (1990s), the first phase goes back to the era of the Momin Conference in Bihar. The Momin Conference (1930s and 1940s) was shaped by nationalist movements and the politics of the Congress.

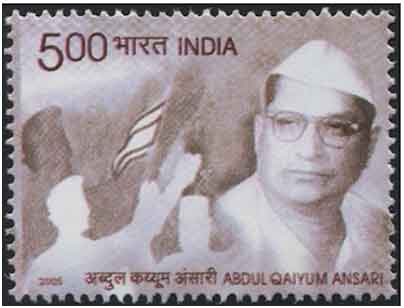

Founded in Kolkata by Bihari Muslims, the Momin Conference rejected both Hindu and Muslim nationalisms. However, the organization could not remain active after Independence when its top leader Qaiyum Ansari (1905-1974) became a minister in the Congress-led Bihar government.

Qaiyum Ansari is considered to be one of the most popular icons of the Pasmanda movement. The Indian government has even issued a postal stamp in his name.

He emerged on the wider political scene in Bihar in the early 1940s, writes historian Mohammad Sajjad in Muslim Politics in Bihar (2014).

Qaiyum Ansari was also the president of the Bihar Provincial Jamiat-ul-Momineen. He joined the freedom struggle during the Khilafat Movement when he came in contact with the Ali Brothers in Sasaram, Bihar. His “assertive” politics in the 1930s and the 1940s opposed the Muslim League and the two-nation theory. After Independence, he became a minister in various Congress state governments (1946-52, 1955-57 and 1962-67) and later the president of the party’s Bihar Pradesh Committee, a member of Congress Working Committee and a Rajya Sabha member (1970-72).

Decades after the death of Ansari, the second phase of Pasmanda movement resumed under the influence of politics of social justice in Bihar..

(After mentioning how various parties linked themselves with PM, he continues:)

…this unity between the oppressed from the Hindu and Muslim folds is based on their “shared suffering”, “dard ka rishta”, common “experience”, “occupation” and “humiliation” inflicted on them by members of the upper castes.

The Pasmanda movement’s slogan “pichhra pichhra ek saman, Hindu ho ya Musalman” (Dalits and backwards are the same whether they are Hindus or Muslims) brilliantly encapsulates this point…

A change in political equation and identity requires reinterpretation of history too. While traditional Muslim scholarship had often ignored the question of caste, the Pasmanda Muslim intellectuals give it primacy. For example, Masood Alam Falahi [Hindustan Mein Zaat-Paat Aur Musalman (2007)] argues that lower-caste Muslims have been discriminated against and denied access to power since the medieval period. Mughal emperors Aurangzeb (1618-1707) and Bahadur Shah Zafar (1775-1862) began to be seen as casteist. Even Muslim icons of modern India such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817-1898), the founder of Aligarh Muslim University, used, it was pointed out, derogatory language against lower-caste Muslims (badzat jolha) and was a protector of upper-caste interests.

By demolishing the ashraf icons, the Pasmanda Muslims constructed new icons, which belonged to the Kabir-Phule-Ambedkar tradition. While they adopted Babasaheb Ambedkar as an icon because of his struggle against the caste system, they put OBC leader Karpoori Thakur right up there with Ambedkar. When he served as Bihar’s chief minister, Thakur gave 26 per cent reservation to the backward castes in which many Dalit Muslim castes were also included.

Besides them, the Pasmanda movement has also adopted new icons from lower-caste Muslim groups. They are Veer Abdul Hamid (1933-1965), who was conferred Paramveer Chakra for his heroic fight during the 1965 Pakistan War; Bismillah Khan (1913-2006), renowned shehnai player and the 2001 Bharat Ratna awardee; Qaiyum Ansari; and Maulana Atikurraham Aarvi, who was a student of Darul Uloom Deoband and a nationalist freedom fighter.

By adopting these icons, Pasmanda Muslims have challenged the hegemony of the upper castes in the sphere of culture and civil society. This invention of a new cultural imaginary is a welcome development in the intensifying Dalitization of public culture.

(First published Forward Press (print edition October 2015), published online January 20, 2016)

*** ***

(The author is a media person who contributed to countercurrents.org.)

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX