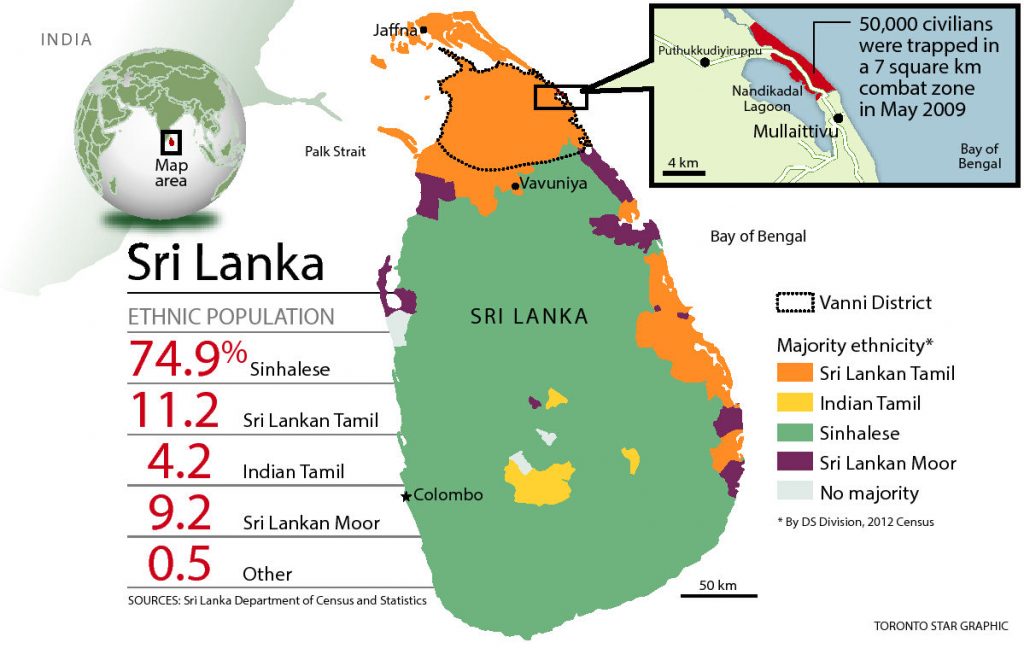

This July marks the 39th anniversary of what became known as Black July. The riots of July 1983 in Sri Lanka would forever alter the course of ethnic tensions in the country, and would lead to the movement of Tamils out of Sri Lanka and into countries like Canada in increasingly dramatic numbers. The riots also marked a decisive shift in the course of ethnic politics in the country as non-violent approaches gave way to Tamil militancy.

At a time when Sri Lankan Tamils were seeking refuge from violence and political persecution of Sri Lanka’s Anti-Tamil Pogrom July 1983. Canada opened its doors to provide a safe haven.

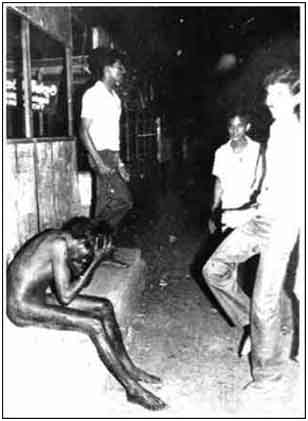

The rioting on this night continued for another week. Hundreds of Tamil and Indian businesses were burned, homes were destroyed, and many were beaten, shot, or burned alive in their houses or vehicles. Many women were raped or forced to exhibit themselves in front of heckling crowds of people. Perhaps the most infamous incident occurred at the Welikade maximum-security prison, about four miles north of Colombo. On the afternoon of July 25, Sinhalese prisoners gained entry into the wing of the prison holding Tamil political detainees and killed thirty-seven of them with knives and clubs while guards stood idly by.

The militarisation of the Sinhala-Tamil conflict in Sri Lanka began in the 1970s when attempts to reconcile by peaceful means the Tamils’ claim for basic individual and collective rights with the Sinhalese need to allay their chronic sense of insecurity finally failed. Since then the struggle has intensified, erupting successively in the burning of the Jaffna Public Library in 1981, the anti-Tamil pogrom in 1983, and the army’s assault on Jaffna in 1995. The mainly Hindu Sri Lankan Tamils have always been separated by language, religion, and history from the Buddhist Sinhalese.

The Sri Lankan government’s response to Black July was dismal. As A.J. Wilson has argued, “President Jayewardene was unequal to the task. At first he seemed numbed and unable to confront the crisis, but he then proceeded from blunder to blunder. He appeared on television on 26 July 1983 with the purpose of assuaging the fears and hysteria of the Sinhalese people, but he did not utter a word of regret to the large number of Tamils who had suffered from Sinhalese thuggery masked by nationalist zeal.” What Wilson calls Jayewardene’s “ultimate blunder,” however, was the passing of the Sixth Amendment in August 1983. The Amendment outlawed support for a separate state within Sri Lanka, and required all Members of Parliament to take an oath of allegiance “to the unitary state of Sri Lanka.”

Tamil shops and premises were being systematically burnt by trained squads. Where Sinhalese premises adjoined Tamil premises, appropriate precautions were taken. Whenever they finished with an area, the expression they used was “We have done the cleansing here”

People were burned alive in their cars, stripped naked. Women were raped. In Colombo and provincial towns, soldiers stood by and even supplied petrol. In two pogroms in the biggest prison, Sinhalese inmates killed 53 of their Tamil counterparts.

There was almost certainly government complicity – a Sri Lankan human rights group says gangs operated at the behest of hard-line ministers.

On 27 July 1983, the then President JR Jayewardene made his first speech on the events, offering no sympathy to the minority and instead emphasizing Sinhala grievances.

More killings followed. By the time the violence dwindled on 31 July 1983, tens of thousands of Tamils had fled to the northern and eastern provinces or abroad.

Black July was a recruiting agent for Tamil militants and catapulted the country into full-blown war, which would last 26 years and kill 100,000 or more people.

It had a drastic demographic effect as hundreds of thousands of Tamils fled abroad, said CV Wigneswaran, a retired Supreme Court judge who has just become a politician for the largest Tamil party.

“With that started the brain drain. A lot of intellectuals, lawyers, doctors, architects, engineers all went away from Sri Lanka. They thought there was no way out,” he said.

“The diaspora today still cannot forget the death, damage, destruction that took place in 1983 because of which they had to leave Sri Lanka and go abroad.”

The idea of a separate Tamil homeland – then as now illegal as a political platform – also became more powerful because so many Tamils fled to the areas of the island where they were the majority.

Kumarathasan Rasingam – Secretary, Tamil Canadian Elders for Human Rights Org.